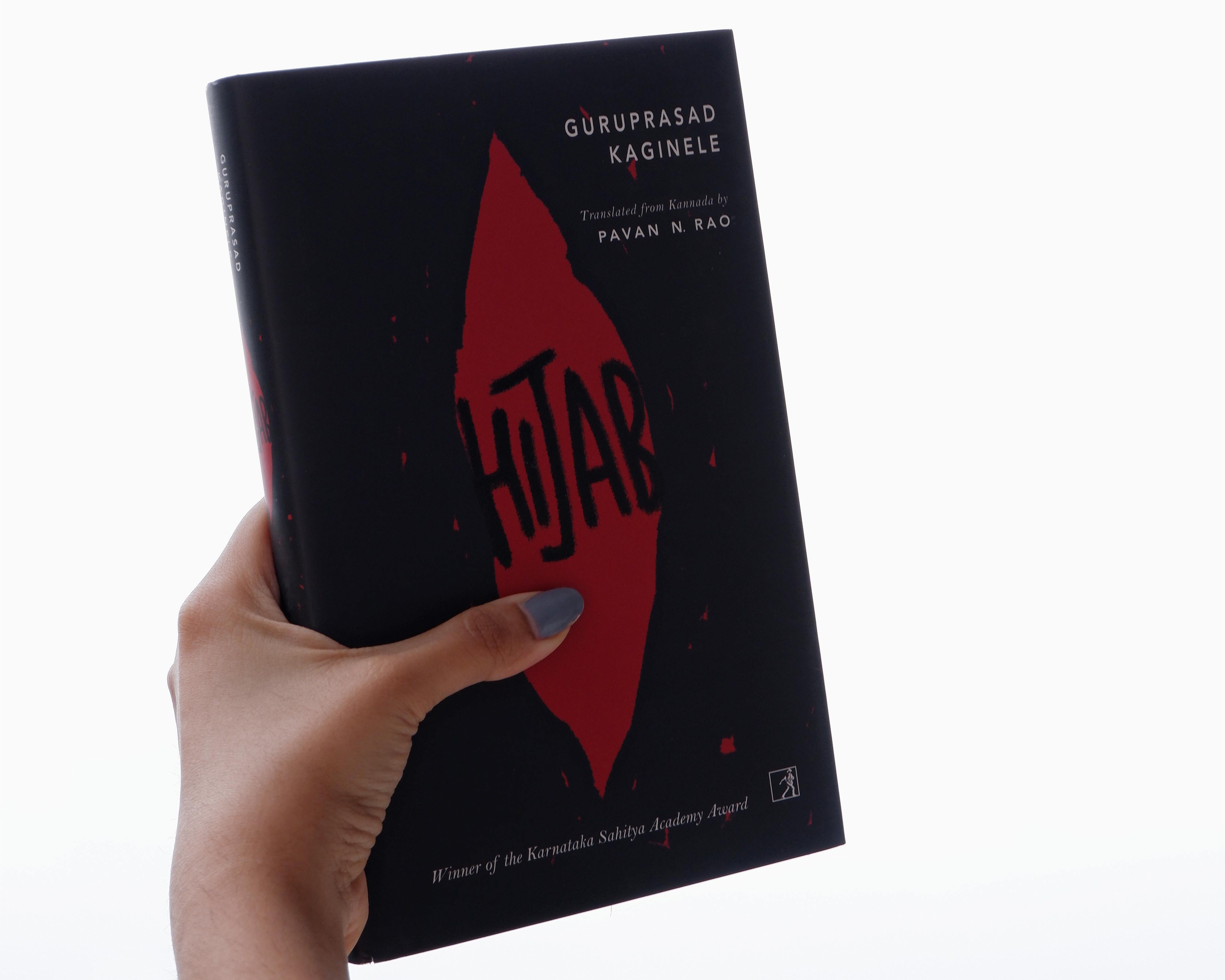

Hijab

by Guruprasad Kaginele, translated from the Kannada by Pavan N. Rao

Publisher: Simon & Schuster India (2020)

My name is Guru. That is not my given name. Yet, that is how I’m addressed by my friends, my coworkers, and my patients. I do have a first, middle and last name. I live in a small town called Amoka in the state of Minnesota, working as an emergency physician in the only hospital in town.

I am also a writer. I’ve written a few short stories and novels in Kannada.

With only these opening lines of the prologue and the information I have gathered about the writer at my disposal, I cannot help but wonder if this novel is semi- autobiographical, set in a fictional loacale. Guruprasad Kaginele’s Hijab, his third novel and his first to be translated to English by Pavan N Rao won the Karnataka Sahitya Academy Award in 2017. Kaginele rather deftly uses the site of a hospital, the only one, we’re told in the fictional town of Amoka, Minnesota, to investigate the many complexities of ‘immigration and integration (Kaginele uses these words to describe his book in an interview with Simon and Schuster)’, nationality, class, religion and science. Each of these could individually be the subject of a book – they are composite problems, rooted in the real world, more often than not without any answers. This is what Hijab offers to the reader.

The book is narrated through the perspective of the chief doctor at the Amoka General Hospital, Guru. Guru’s world revolves around the hospital, his two flatmates, Srikantha and Radhika. Very early on in the novel, he reveals that the three of them have been posted in the remote town on duty – a necessary pre requisite to obtain their green cards. The town also has an influx of refugees from Sanghaala, a fictional country, bringing to Amoka a sizeable Muslim population. In the same aforementioned interview with Simon and Schuster, Kaginele talks of two kinds of immigration – the first being immigration for a better life and the other, ‘immigration for sustenance.’ This dichotomy plays out in the relationship that the three Indian doctors share with the land that will soon become their home, America and the Sanghaali community and vice versa.

The novel begins rather ominously. A Sanghaali patient, Fadhuma, is admitted to the hospital with labour pains and it is established at the outset that this is not going to be a natural birth but a cesarean section. What is also revealed is the Sanghali community’s vehement opposition to this procedure. Guru’s attempts to communicate with the patient and the absence of a Sanghaali translator make for a rather dramatic opening. The drama that unfolds through the first part of the novel is the circumstances that follow Fadhuma’s delivery, where cultural beliefs and scientific/medical reasoning clash. Kaginele leaves a lot of plot holes open in the first half, which I assumed would be tied up in the second half, which take place two years later. However, this is where the novel surprises the reader.

The characters in the novel have moved on and the astounding events that the first half of the novel centred around remain nothing but a blip in public memory. In this section, the novel attempts to foray into the larger themes that the novel is centred around. The plot here is not the focus as it was in the first half. The point rather becomes several questions that the characters raise in the second half of the novel. For instance, Guru asks himself – “If I were to be observed without the halo of a physician, do I do things differently based on skin colour?” So my prejudices, values and experiences drive me towards this kind of behavior?” Or when Nusrat rather bluntly asks, “Is there any resemblance what so ever between him and my son? If he were to be a white person, would the police have shot him?”

What Kaginele’s novel does effectively is raise uncomfortable questions. However, there is no answer to these questions, even those that could have perhaps had some closure, plot wise. This makes me wonder if Kaginele intended to keep these plot points open ended, so the novel, like reality, offers the reader more questions, not solutions.

RELATED ARTICLESMORE FROM AUTHOR

Can’t

Minor Disturbances at Grand Life Apartments

Adam