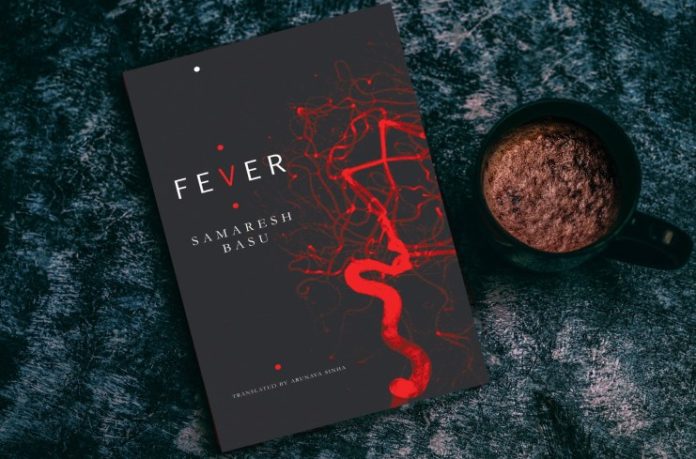

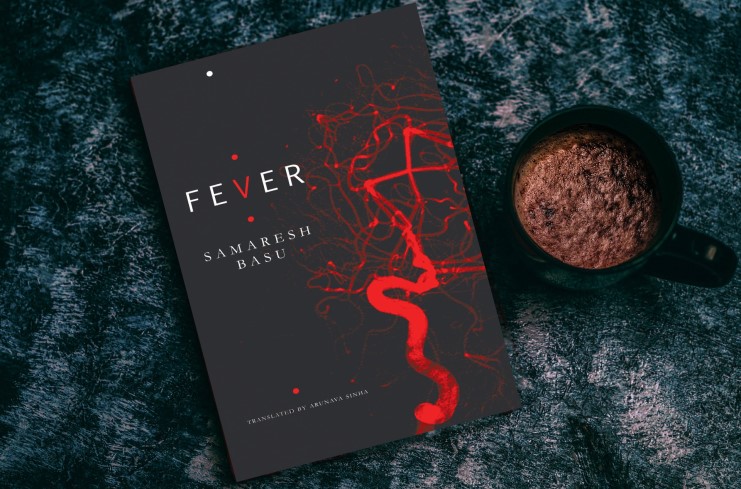

Fever

by Samaresh Basu (translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha)

Publisher: Penguin Random House India (2012)

“Those who had shared this belief had destroyed everything around them in their conviction” (Basu, Sinha 123). A single, simple statement: the truth of Ruhiton Kurmi’s shackled-then-freed Adivasi, revolutionary existence traverses from Samaresh Basu’s Bengali novel, Mahakaler Rather Ghoda (Horse to the Chariot of Time) to Arunava Sinha’s scrupulous English translation retitled Fever. It’s a text bathed in tremulous, painstaking shades of every red—scarlet, crimson, rust, amber—of (dried and drying) blood, itching sores, despairing anger, volatile passions. And of course, the perforated, sickle-bearing flag of the Naxalite Movement.

The novel takes the charged body politic theatre of ‘70s Bengal and zeroes its acute gaze onto one (ailing, imprisoned) man, unpacking him fully: he is always moving, carted from one prison to another for years on end believing he is to finally rest with his encounter but he doesn’t find this peace. He’s taken through time and memory instead, immersed in his experiences of an uncertain childhood, a past forgotten and looking forward through the haze of a barely surviving present into the mute possibilities of a scarce future … there seems to be no destination. He dwells upon his crimes, sharpened through their treasonous, violent overtones (not entirely without remorse) and remembers his leftist identity with proud conviction but his leathery skin is weathered and softened with the tender affect of his wanting to be again, a (fleeting) lover, (nostalgic, deserving) husband and a (stranger, adoring) father to his three (no-longer-) children.

He’s a person apart from the others, pockmarked with reddish rings all over his body—he is increasingly ill, bouncing from one and the same space to another till he settles into his newest ‘home’ (if you will), happier than he has been in a while between his equals, his fellowmen. Or so he would believe. Sooner than he’d, (even we’d want to) believe … his folk hero-ness among his comrades, is eclipsed by their suspicion of his disease. The question is what is this ‘sickness’? Of course, there’s the medical diagnosis—it’s leprosy, turning his fingers into scapes of gangrene, eating away at his skin. It’s contagious hence, the enforced solitary quarantine. But what more?

As you would’ve gathered, the affliction is metaphorical, making Kurmi an outsider even among who he thought were his people. Khelu Chowdhury betrays him, looking after his own flock of men—they’re ‘clean’, they’d have us believe. Cleaner than Kurmi from his infection, cleaner than Kurmi for being of ‘better’ breeding, ‘better’ class, caste background? Now, isn’t that ironic—the (Commun/Mao)ism championed through the symbol of Basu’s chariot, the horses of the pawns in the bigger game, the workers—had driven with their labour broke the creatures’ back with its ideological weight after all. The phyla of the (Indian) Homo sapien wormed and wriggled its truths into what was meant to be an imagined socio-political shelter for those deemed lesser, creating fissures, casting out one man and then another …

It wasn’t just the prisons with their third-degree interrogative techniques that was a far cry from the promised, classless paradise. The ahimsa-ic real world was another kind of nightmare, at least for Rohinton Kurmi. Even healed from his leprosy, he can’t integrate. His Mangala, his sons and daughter are married now, living in the big house over the way … the government is looking after them, the family of a man (are they even his family anymore, really?) who had been thrown in jail for active rebellion, treason. Nothing is the same, though everything is. The neighbours, Kachimuddin, Dil Narayan, the Chhetris—seven years, and “Ruhiton could sense that none of these people belonged to his world … all seemed to be traders or landowners” (Basu, Sinha 115)—it never struck Kurmi that maybe he didn’t belong in theirs.

Historically, we know what happened. The Naxalite Movement itself, was sold out by those at the very pinnacle of its hierarchy, those seated within the comfort of the palanquin, leaving the men on ground to their devices, unknowing, blinded by their “superiors’” once faith-filled promises, journeying, protesting, marching fruitlessly, being slaughtered at the butchers’—it’d make anyone bitter. Kurmi had wanted to believe even then, hoping that their sacrifices hadn’t been in vain … but it certainly seemed that way, it was how the narrative played out on the real political stage whilst the pawn-players were being doused in frigid waters, shocked, beaten, broken behind bars. An ugly on-going end, but ultimately, the one implemented.

So, what makes this novel, Mahakaler Rather Ghoda, Fever have particular resonance today? What are its stakes, why did I choose this text to review? The answer will be apparent enough if you look beyond the screen, at the window to the banners fluttering in the air ‘round the world. Fascism is reigning, its chokehold cutting off air to our lungs more and more every day. We are being blindsided to the ‘truth’, being fed it, soaked in colours of propaganda and blood. And those that are on the field tonight, every night are thrown to the wolves.

Make no mistake, these are only analogous sketches—Naxalism has been displaced, the chariot is now, more gaudy, gold-furnished, it’s what we conceive of as the State (read: the government), the nationwide, financial crème de la crème, the pan-Indian bhadralok (only in name, not action); we’re the toiling horses. Some baulking, some straining to get free, others obediently tugging the chariot along (are these beasts the equine ghoda or the base gadha?)—but most though disillusioned, are still tethered to the rath, still inextricably within the system.

Well, at least our saving grace is that we know. Rohiton didn’t. He trusted those that would eventually betray him, he was certain of their purity of intent, till he wasn’t. And immersing oneself in the narrative, witnessing the shattering of the faith he had had, it evokes not just pity, sympathy but empathy. Add to this his estrangement from his family—and we’re reading a tragedy, not Aristotelian in epic proportions but devastating much, much closer to home.

So yes, I would recommend Fever, not by a long shot for light reading but instead, especially appropriate for our current political circumstance rife with prejudice, bigotry, hatred. In it you’ll find the (beautifully, somehow delicately) rubbed raw texture of the battered psyche of a human being, who has struggled, fought, been stripped of everything but still strives to resist, to belong, to (dare I say?) hope.

I’m not guaranteeing you any sort of ‘happy’ ending, but in it there’s an unexpected gentleness … is it Ruhiton Kurmi surrendering, delivering up his spirit? Prophesying the futility of this struggle? Or a guiding passage into the future, closing this failed chapter of historic revolution only to aspire for a newer one, where we’ll do better? That’s the question, I found myself asking, and maybe you will too.

RELATED ARTICLESMORE FROM AUTHOR

Can’t

Adam

The Odd Book Of Baby Names