The Book Of Everlasting Things

by Aanchal Malhotra

Published by Harpercollins India (2022)

The boy from the ittar shop meets the pistachio-eyed calligrapher- at first glance, this might seem like a sweet moment from a romantic novel. It is that, but it is also a novel of many facets, with varied proportions of history, memory, fragrances and feelings blended in delicate concoctions to create a novel composition of everlasting storytelling. The story affirms the truth in the well-worn phrase— “the personal is political”, showing that when the tides of history shift, decade-old relationships can become collateral victims of the greater forces at play.

The Book Of Everlasting Things revolves around the Vij and the Khan families, custodians of the traditional crafts of perfumery and calligraphy, respectively. Their young scions and protagonists of the novel are Samir Vij and Firdaus Khan, who are shaped by the essence of scent and script. Set against the backdrop of a vibrant, syncretic Lahore, their romance blossoms into a profound connection transcending societal boundaries—a love woven from deep understanding, shared experiences, and sensory memories. Amidst the casual disposability of modern relationships and of “No strings attached” arrangements, theirs is something enduring, an intimacy that restores your faith in eternal love.

Samir and Firdaus’s romance feels like the refreshing breath of petrichor after the first monsoon shower, a fitting analogy given Samir’s description as a “monsoon child.” His love language is rooted in smell; he memorizes his beloved’s fragrance and spends years meticulously constructing a new one for her. Smell plays a visceral role throughout the narrative, the novel serving as a portal to the invisible world of sensory experience. Through the storytelling, the reader learns to perceive smell, feel its subtle nuances, and understand its intricate textures. The narrative unveils how smell can be both an emotional anchor and a repository for intimacy, history and memory.

The strong connection to the sensory world and the depth of emotional expression are hallmarks of Malhotra’s male characters, who embody an increasingly celebrated archetype marked by emotional complexity and a clear rejection of traditional masculine stoicism. Her work joins a vital body of Indian contemporary literature that features deeply human portrayals of men. These men are a striking departure from the emotionally distant, action-oriented heroes that have historically dominated mainstream narratives. They are layered, possess rich inner lives, demonstrate emotional intelligence, and embrace vulnerability, loving with a fierce intensity.

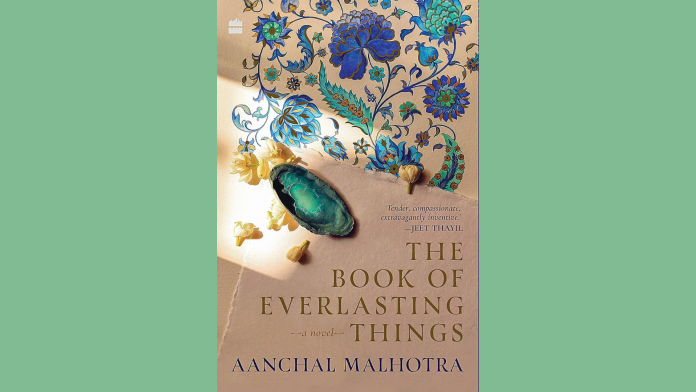

While “Show, don’t tell” is a cornerstone of good writing, The Book Of Everlasting Things takes it further- it also smells. The ittars, such as rose, vetiver, and sandalwood, are so meticulously detailed in the lush, lyrical, and evocative prose that the sentences themselves seem aromatic. This sensory richness is a testament to the painstaking research and six years of emotional investment poured into its creation. The author’s proclivity for detail and sensory richness even blooms upon the book’s cover, a vibrant tapestry of ancient manuscripts and delicate botanicals, drawing inspiration from the exquisite naqqashi patterns and the intricate foliage motifs adorning Lahore’s Wazir Khan Mosque, considered to be the most ornately decorated Mughal-era mosque. The commitment to sensory and historical authenticity is also visible within the narrative, drawing from the legacy of century-old distilleries in Kanauj and Kashmir’s legendary rosewater shop, Kozgar’s Arq-e-Gulab, grounding the novel’s fragrance-filled world in real artisanal traditions.

What starts as a celebration of craft and fragrance gradually unfolds into a poignant exploration of history, memory, and loss. The novel uncovers how communal discord is often seeded through seemingly minor suspicions and distrust, grows into towering forces of division that fracture the very soil that nurtured them. As an oral historian specialising in Partition narratives, the author has a remarkable ability to humanise grand historical events. This is strongly depicted in her portrayal of ordinary lives upended by Partition, as well as her resurrection of figures like the Indian sepoy during World War I, who had previously been moved to historical footnotes.

Malhotra combines historical insight with empathetic storytelling to shed light on how political violence disrupts human relationships, echoing American author Kristin Hannah’s The Nightingale, where war tests love and loyalty. Although differing in geographic and cultural contexts– The Nightingale is set in Nazi- occupied France and The Book Of Everlasting Things during Partition– both works ask the same question: what happens to love and family when history turns catastrophic? A fundamental truth that emerges from both these narratives is that historical trauma spills beyond battlefields into domestic spaces, reshaping personal lives and leading individuals to reconstruct their sense of identity and belonging. It is precisely within this reconstruction that Malhotra’s novel raises another poignant question: Is home that intangible yet deeply felt sense of belonging, or is it rooted in physical geography, the land of one’s birth, shaped by ancestral memory, cultural inheritance, and the histories inscribed in its soil? The tension between rootedness and rupture recalls a moment in Annie Zaidi’s essay Bread, Cement, Cactus where she reflects on freedom and belonging by quoting an Urdu translation from Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude: “Jahaan koyi apna dafn na hua woh jagah apni nahin hua karti”—a place where none of your own are buried can never truly be your own. In Malhotra’s world, this idea reverberates through the lives of lovers separated by borders and beliefs.

The intermingling of the personal and the historical underpins the novel’s underlying complexities. For instance, take its exploration of the interplay between memory and history, framing absence as the most persistent form of presence. This idea resonates with a recurring motif in venerated poet Agha Shahid Ali’s work: “Your history gets in the way of my memory”, an iconic encapsulation of how personal recollections are entangled with documented narratives. The notion finds a deeper texture when Malhotra writes, “Things hardly rupture in clean lines.” Pain, loss, and memory don’t follow neat trajectories: the act of remembering is seldom linear and is often accompanied by forgetting. History, then, becomes a layered landscape– one in which memory continuously reframes how we interpret the past.

Through a lens of messy, multifaceted memory and history, The Book Of Everlasting Things powerfully rehumanizes Partition. The novel offers a gentle contrast to history told in dry, detached timelines and facts, instead bringing to life the lived realities and deep losses of ordinary individuals on either side of a land divide. It’s an important meditation on empathy, serving as a vital counterpoint to a modern world awash with quick judgements, stereotypes, and dehumanisation. This approach to history and human experience highlights a critical truth: how we remember is as vital as what we remember. In doing so, the novel honours cultural heritage, conveying the deep emotional significance held by the physical objects of our past. Finally, The Book Of Everlasting Things extends an invitation: to hold history and memory with complexity, care, and compassion. It provides a valuable antidote to the hustle and bustle of contemporary existence, asking us to make room for nuance, for tenderness, and for remembering the everlasting imprints of our shared humanity.

RELATED ARTICLESMORE FROM AUTHOR

Swallowing the Sun

Death of a Gentleman

Sinema: : The Bollywood Bungle of Andy Duggal